The industrialised world’s patterns of consumption and production are wasteful and unjust – and we’re all living with the consequences in the form of climate change.

The Global Resources Outlook shows why we must adopt the more future-fit economic models available to us, which offer multiple benefits for people and planet.

The Global Resources Outlook 2024 (GRO24), published today by the UN International Resource Panel, brings together the best available data, modelling and assessments to analyse trends, impacts and distributional effects of resource use. The IRP’s co-chair, Janez Potočnik, sums up the messages and calls on policy makers to act on the link between resource efficiency and climate.

This new Global Resources Outlook from the International Resource Panel is vital to the future of our planet. It shows how current patterns of resource use are driving today’s triple planetary crisis. It reveals how those patterns stem largely from consumption and production behaviours in the industrialised world, making them unjust as well as wasteful. And it offers a pathway to a fair and sustainable future based on changing those behaviours.

The 2024 Outlook makes clear that if we don’t change our patterns of resource use now, we will not only face increasingly severe environmental consequences, but miss opportunities to advance human wellbeing. These conclusions from IRP’s scientists are in line with research from across the climate, environment and social science community.

”We need to recognise that meeting human needs does not depend on ever-increasing resource use, especially in high-income countries... The 2024 Outlook offers a fair and sustainable future, based on changing our consumption and production.

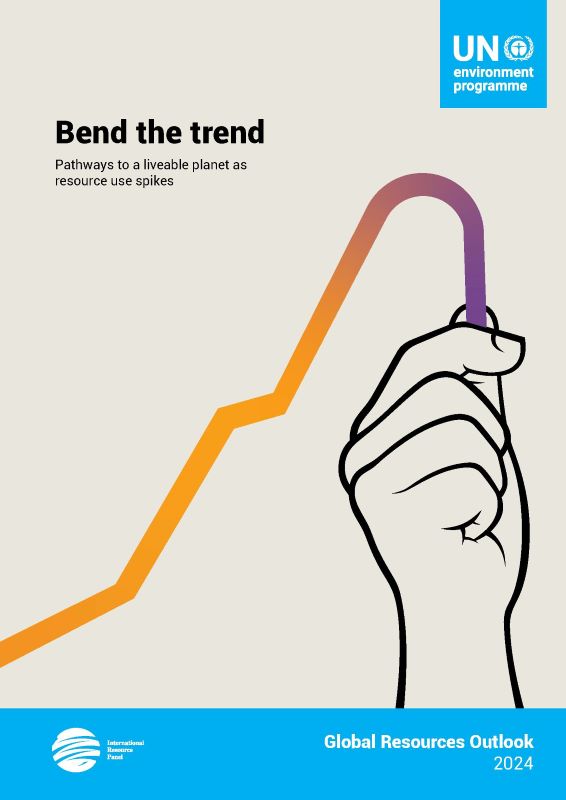

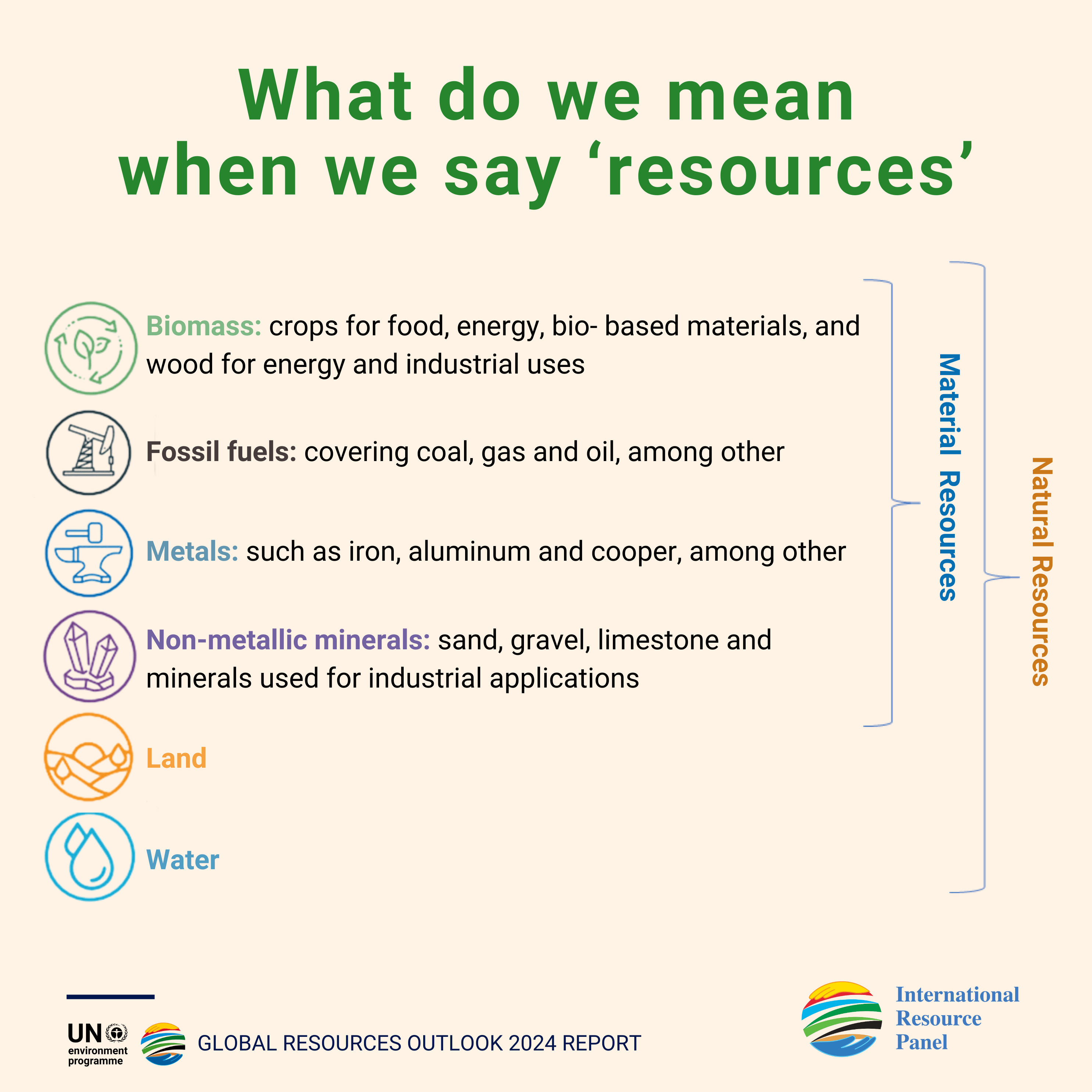

The triple planetary crisis describes the dangerous intersection between climate change, loss of biodiversity and nature, and pollution. IRP’s new research shows that the extraction and processing of materials now lies behind:

- 60% of adverse climate impacts (including impacts relating to land use change);

- more than 90% of the loss of biodiversity and water stress related to land use; and

- around 40% of particulate matter pollution affecting health.

Sadly, all three numbers have continued to rise since our last global assessment in 2019. Indeed, since 1970, total global material use has more than trebled. And unless current trends are tackled, it will continue to grow from about 100 billion tons in 2020 to 160 billion in 2060.

The world’s wealthiest benefit most from today’s pattern of resource use, as well as being responsible for most of its adverse environmental impacts. Meanwhile, many low-income countries still do not consume enough material to meet basic human needs. We clearly point out the importance of the huge differences between different income groups in material footprint terms, which includes domestic extraction and net material trade balance. IRP’s scientists have explored what causes these unsustainable patterns, and point the way towards fundamental, systemic solutions.

”We are simply setting the order right: the economy was invented to serve humans and not the other way around.

We need to shift away from linear “produce, consume, discard” approaches to resource use, and instead become circular and resource-efficient societies, optimising wellbeing for all. To avoid severe environmental impacts, breaking the links between ever-increasing resource use, economic development, human wellbeing, and environmental impacts – what is termed decoupling of economic and wellbeing growth from resource use and environmental impacts – is a must.

In high-income countries, absolute decoupling should be the aim: decreasing material use, while maintaining or improving wellbeing outcomes. In low- and some middle-income countries, where additional material use is still needed to build up infrastructure and meet people’s basic wellbeing needs, relative decoupling should be the aim. This is necessary and also just.

In GRO24, we are simply setting the order right: the economy was invented to serve humans and not the other way around. So, we look at how to optimise provisioning systems and human needs, rather than maximising the output of individual sectors. We acknowledge the usefulness of GDP, but we should be guided by wellbeing. We propose to focus on the most resource-intensive provisioning systems – the built environment, mobility, food and energy – which represent 90% of global material demand. Focusing on human needs would allow and incentivize cross-sector innovation and shifts to a more future-fit business models.

When businesses understand the essence of the challenge, and dare to be innovative, decoupling is also a major opportunity. We need to recognise that meeting human needs does not depend on ever-increasing resource use, especially in high-income countries. Increasingly, they will reward responsible, innovative, creative ways of meeting human resource needs without stimulating extraction. Growing demand for circular resource systems will incentivize cross-sector innovation. The resulting shift to resource-light business models can deliver innumerable benefits for the planet and its people.

Supply-side polices currently receive most of the policy attention. But they should be complemented with demand- and consumption-related policies. And resource efficiency policies should be complemented with a resource sufficiency perspective.

The Sustainability Transitions scenario in our report details a pathway for tackling long and short-term economic problems while improving environmental outcomes and increasing equality. It shows how to pursue such a pathway – one which maintains, and in many areas enhances, human wellbeing without breaching planetary boundaries. But this is only possible if we fix our broken compass and change direction now!

So far, the climate change part of the triple crisis has attracted most attention from policy makers, and with good reason. But their supply-side measures to decarbonise economies are having limited success. According to Statista, global CO2 emissions in 2023 were higher than ever before. The Copernicus Climate Change Service tells us that in the same year, the average global surface temperature was already close to more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above its pre-industrial level. And perhaps most worrying, according to the IMF, fossil fuel subsidies topped $7 trillion or 7.1% of global GDP in 2022, the highest-ever level.

Clearly, supply-side climate solutions are not enough. IRP’s new GRO24 confirms that climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution can be effectively addressed – but only by combining supply- and demand-side solutions to encourage changes in consumption and decoupling, and nature-based solutions to harness the potential of eco-system services and natural carbon sinks.

Our modelling is showing that, with systemic shifts, we can mitigate growth in material use by 30% by 2060, and reduce total global energy demand by 25% by 2060, both compared to today’s levels … all consistent with global decarbonisation goals.

”We should embrace the words of Mahatma Gandhi: 'The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not for everyone’s greed.'

Decarbonisation and decoupling must go hand in hand. We need consistency in how we try to solve the climate crisis and to meet other environmental and social challenges. This would also make energy transition easier and feasible.

A recently published scientific paper, “The behavioural crisis driving ecological overshoot”, supports this position. Its authors say that “climate breakdown is a symptom of ecological overshoot, which in turn is caused by the deliberate exploitation of human behaviour. We need to become mindful of the way we’re being manipulated. The material footprint is dangerously underdiscussed. Most climate ‘solutions’ proposed so far only tackle symptoms rather than the root cause of the crisis.” This, they say, leads to increasing levels of the three ‘levers’ of overshoot: consumption, waste, and population. Where discussion of climate often centres on carbon emissions, a focus on overshoot highlights the materials usage, waste output and growth of human society, all of which affect the Earth’s biosphere.

Presenting the GRO24 at the United Nations Environment Assembly

Clearly, this latest outlook from the International Resource Panel is in tune with other experts on the planetary crisis: notably, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPPC), the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), and the Global Environment Outlook (GEO). Their work, like ours, is based on the most comprehensive scientific assessments. Taken together, these must be considered as a statement of urgency from the scientific community.

In short, much of the relevant scientific community now supports the same vision: we should aim to live well within planetary boundaries; we should aim for meaningful and decent lives for all. We should embrace the wise words of Mahatma Gandhi – “The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not for everyone’s greed” – and use them as an inspiration for our work and actions.

The equity implications of resource use are critical if we are sincere in our quest for a more sustainable and just world. With decisive action and political courage, a sustainable future for all is still possible, but the solutions pathway is getting narrower and steeper, and there are fewer, and more urgent options on our policy menu than there were decades ago.

We are indebting future generations, financially and by depleting Nature. This is simply wrong. Apparently, we humans are the most intelligent species on this planet; it is high time to prove it. More than an economic or a technological choice, this is indeed a moral choice. One thing is clear: the future will be green… or there will be no future.